Chuck Jones

| Chuck Jones | |

|---|---|

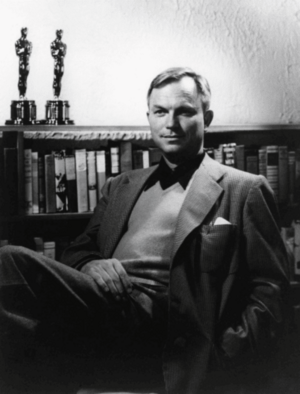

Jones, circa 1930s. | |

| Born | Charles Martin Jones September 21, 1912 Spokane, Washington |

| Died | February 22, 2002 Newport Beach, California |

| Cause of death | Heart failure |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Animator Director Writer Producer |

| Crew credits | Director of various Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies cartoons Creator of Wile E. Coyote, the Road Runner, Pepé Le Pew, Penelope Pussycat, Marvin the Martian and other characters |

Charles Martin Jones (September 21, 1912 – February 22, 2002) was an American animator, painter, voice actor and filmmaker, best known for his work at Warner Bros. Cartoons, namely the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series of theatrical shorts. He was credited for writing, producing, and/or directing various classic animated shorts starring Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Porky Pig, among others. He was also known for creating some iconic Looney Tunes characters, including Pepé Le Pew and Penelope Pussycat, Marvin the Martian, Witch Hazel, Michigan J. Frog, Sam Sheepdog and Ralph Wolf, Hubie and Bertie, the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote.

Jones started his career in 1933 at Leon Schlesinger Productions, the studio that made the Warner Bros. shorts, alongside Tex Avery, Friz Freleng, Bob Clampett, and Robert McKimson. During the Second World War, Jones also directed several of the Private Snafu shorts which were shown to members of the United States military. His initial career at Warner Bros. ended in 1962, of which he started Sib Tower 12 Productions and began producing cartoons for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, including his run on Tom and Jerry (1963-1967), the television adaptation of How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1966), and the 1970 film adaptation of Norton Juster's The Phantom Tollbooth. He later started his own studio, Chuck Jones Enterprises, where he mainly focused on directing and producing television specials. From 1976 to 1997, he returned to Warner Bros. to contribute a handful of Looney Tunes projects.

Jones' animated films are highly recognized as classics of the form, and including Feed the Kitty (1952), Duck Amuck (1953), One Froggy Evening (1955), and What's Opera, Doc? (1957).[1] Three of his films, For Scent-imental Reasons, So Much for So Little, and The Dot and the Line, won the Best Animated Short category of the Academy Awards. In Jerry Beck's The 50 Greatest Cartoons, a group of animation professionals ranked What's Opera Doc? as the greatest cartoon of all time, with ten other entries being Jones' Duck Amuck, Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century, One Froggy Evening, Rabbit of Seville, and Rabbit Seasoning among others.

Jones passed away of a congestive heart failure on February 22, 2002, at the age of 89.

Biography

Early life

Jones was born on September 21, 1912, in Spokane, Washington to Mabel McQuiddy (née Martin) and Charles Adam Jones.[2] When he was six months old, he moved with his parents and three siblings to Los Angeles, California.[3]

In his autobiographies, Chuck Amuck and Chuck Reducks, Jones attributes his artistic influence to circumstances surrounding his father, who was an unsuccessful businessman in California in the 1920s. He recounted that his father would start every new venture by purchasing stationery and pencils with the company name on them. When the business didn't work on his father, he would quietly turn the huge stacks of useless equipment over to his children, requiring them to use up all the material as fast as possible, The children drew frequently, owing to the abundance of high-quality paper and pencils. Later, during an art school class, Jones' professor informed the students that they each had 100,000 bad drawings that they must get past before they could possibly draw anything worthwhile. Jones recounted that this proclamation came as a great relief to him, as he was well past the 200,000 mark, having used up all that stationery. Jones and several of his siblings went on to have artistic careers in their lifetime.[4][5]

Jones worked in a part-time job as a janitor during his artistic education. After graduating from Chouinard Art Institute, Jones received a phone call from Fred Kopietz, a friend of his whom had been hired by the Ub Iwerks studio and offered him a job. He worked his way up in the animation industry and started out as a cel washer. He recalled that he "moved up to become a painter in black and white, some color. Then I went on to take animator's drawings and traced them onto the celluloid. Then I became what they call an in-betweener, which is the guy that does the drawing between the drawings the animator makes."[6]

Career at Warner Bros.

Jones was later put as an assistant animator at Leon Schlesinger Productions in 1933, being hired by Leon Schlesinger after the departure of Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising. In 1935, he was promoted to animator and assigned to work with a new director, Tex Avery. Under Avery's unit, Jones worked alongside fellow animators Bob Clampett, Virgil Ross, and Sid Sutherland, and worked on a small, beat-up bungalow they dubbed "Termite Terrace".[7] He would often work alongside Clampett and serve as one of his key animators once the latter was promoted to director. When Frank Tashlin first quit Warner Bros. in 1938, Jones himself became a director (or "supervisor", the original name for an animation director in the studio). The following year, Jones created his first major character, Sniffles, a cute mouse who went on to star in twelve animated Warner Bros. shorts.

Jones initially struggled in terms of his directorial style. Unlike the other directors of the studio, his early films tended to be more experimental with abstract designs and follow a Disney-esque formula, often focusing more on visuals over humor. Jones wanted to make cartoons that would emulate the quality and design to that of the ones made by Walt Disney Productions,[1] but his films suffered from sluggish pacing and a lack of clever gags; Jones admitted in retrospect that his early conception of timing and dialogue was "formed by watching the action in the La Brea Tar Pits."[8] Schlesinger and the studio heads were unsatisfied with his work and demanded that he make cartoons that were more funny.[9] Jones responded by creating the 1942 short The Draft Horse. The cartoon that was generally considered a turning point of his career was that year's The Dover Boys at Pimento University, of which his comedic timing had been refined at that point. Despite this, Schlesinger and the studio heads were still dissatisfied and had planned on firing him, but were unable to find a replacement due to a labor shortage stemming from World War II, so Jones kept his position.

Jones created characters through the late 1930s to the 1950s, which include his collaborative help in co-creating Bugs Bunny, and also created Cladue Cat, Hubie and Bertie, Marc Antony and Pussyfoot, Charlie Dog, and Gossamer. His four most popular creations are Marvin the Martian, Pepé Le Pew, Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner. Jones and writer Michael Maltese frequently collaborated on the Road Runner cartoons among other shorts like Duck Amuck, One Froggy Evening and What's Opera, Doc? Other notable staffers whom Jones worked with include rotating writer Tedd Pierce; layout artist, background designer and co-director Maurice Nobel; animator and co-director Abe Levitow; and animators Ken Harris and Ben Washam. During World War II, Jones closely worked with Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, to create the Private Snafu series of Army educational cartoons.

Jones remained at Warner Bros. throughout the 1950s, with an exception of his absence in 1953 when the company closed the animation studio. During this interim, he briefly worked with Ward Kimball under Walt Disney Productions, for a four-month uncredited position on Disney's Sleeping Beauty (1959). When Warner Bros. reopened the studio, Jones was rehired and reunited with most of his unit.[10]

In the 1960s, Jones and his then-wife Dorothy wrote the screenplay for the animated feature Gay Purr-ee, which was produced by UPA and directed by his former Warner collaborator, Abe Levitow. Jones moonlighted to work on the film despite his exclusive contract being locked for Warner Bros. at the time. UPA made it for distribution for 1962, but when Warner Bros. picked up the film's distribution rights, they discovered that Jones had violated his contract and terminated him. Jones' former animation unit was laid off after completing The Iceman Ducketh, and the rest of the Warner Bros. Cartoon studio was closed in early 1963.[11]

Later years

Following Jones' firing from Warner Bros., he started an independent animation studio, Sib Tower 12 Productions, with business partner Les Goldman. He brought on most of his former unit from Warner, including Maurice Noble and Michael Maltese. From 1963 up until 1970, Sib Tower 12 worked on various projects such as its run on the Tom and Jerry cartoons, following its previous run with Gene Deitch; the 1964 short The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics; and television adaptations of the Dr. Seuss books, How the Grinch Stole Christmas! and Horton Hears a Who. In 1964, Sib Tower 12 was absorbed by MGM and renamed MGM Animation/Visual Arts. Jones continued to work on television productions, but his main focus during this time was making a film adaptation of The Phantom Tollbooth, which was distributed by MGM in 1970.

When MGM closed the animation division in 1970, Jones once again started his own studio, Chuck Jones Enterprises. He produced a Saturday morning children's TV series for ABC titled Curiosity Shop, and several animated specials such as his adaptations for Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Book stories: Mowgli's Brothers, The White Seal and Rikki Tikki Tavi. In 1971, Jones collaborated as an executive producer for Richard Williams' short adaptation of A Christmas Carol, adapting Charles Dicken's novella and directed by the latter.

Jones resumed working with Warner Bros. in 1976 with a TV adaptation of Camille Saint-Saëns' Carnival of the Animals, starring Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck. He also produced The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie, which compiled a selection of his best shorts, new Road Runner segments for The Electric Company television series and the specials, Bugs Bunny's Looney Christmas Tales and Bugs Bunny's Bustin' Out All Over. Jones' final Looney Tunes short was From Hare to Eternity in 1997, which was dedicated to Friz Freleng, who died in 1995. Jones' last animated project was a series of 13 short starring Thomas Timber Wolf, which he designed in the 1960s. The series was released online by Warner Bros. in 2000.[12]

Following his death on February 22, 2002, at his home in Corona del Mar, Newport Beach, he was cremated and his ashes were scattered at the sea.[3] In memoriam of his passing, Cartoon Network aired a 20-second segment tracing Jones' portrait with the words "We'll miss you." In 2004, Daffy Duck for President, an animated short based on Jones' 1997 book of the same name, was released as part of disc three of the Looney Tunes Golden Collection: Volume 2 DVD set.

Credits

- Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies

- The Miller's Daughter (1934) - animator (as Charles M. Jones)

- Those Beautiful Dames (1934) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Buddy of the Legion (1935) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- My Green Fedora (1935) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Buddy Steps Out (1935) - animator (as Chas. Jones)

- The Lady in Red (1935) - animator (uncredited)

- A Cartoonist's Nightmare (1935) - animator (uncredited)

- Hollywood Capers (1935) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Gold Diggers of '49 (1935) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Page Miss Glory (1936) - animator (uncredited)

- The Blow Out (1936) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Plane Dippy (1936) - animator (uncredited)

- I'd Love to Take Orders from You (1936) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- I Love to Singa (1936) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Porky the Rain-Maker (1936) - animator (uncredited)

- Milk and Money (1936) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Don't Look Now (1936) - animator (uncredited)

- The Village Smithy (1936) - animator (uncredited)

- Porky the Wrestler (1937) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- I Only Have Eyes for You (1937) - animator (uncredited)

- Picador Porky (1937) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Porky's Duck Hunt (1937) - animator (uncredited)

- Ain't We Got Fun (1937) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Porky and Gabby (1937) - writer and animator (as Charles Jones, uncredited as writer)

- Uncle Tom's Bungalow (1937) - animator (uncredited)

- Porky's Super Service (1937) - assistant director and animator (as Charles Jones, uncredited as assistant director)

- Porky's Badtime Story (1937) - assistant director and animator (as Charles Jones, uncredited as assistant director)

- Get Rich Porky (1937) - assistant director and animator (as Charles Jones, uncredited as assistant director)

- Rover's Rival (1937) - assistant director and animator (as Charles Jones, uncredited as assistant director)

- Porky's Hero Agency (1937) - assistant director and animator (as Charles Jones, uncredited as assistant director)

- Porky's Poppa (1938) - assistant director and animator (as Charles Jones, uncredited as assistant director)

- What Price Porky (1938) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Porky's Five & Ten (1938) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- Porky's Party (1938) - animator (as Charles Jones)

- The Night Watchman (1938) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Dog Gone Modern (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Robin Hood Makes Good (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Prest-O Change-O (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Naughty but Mice (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Old Glory (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Snowman's Land (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Little Brother Rat (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- The Little Lion Hunter (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- The Good Egg (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Sniffles and the Bookworm (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- The Curious Puppy (1939) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Mighty Hunters (1940) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Elmer's Candid Camera (1940) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Sniffles Takes a Trip (1940) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Tom Thumb in Trouble (1940) - director (as Charles Jones)

- The Egg Collector (1940) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Ghost Wanted (1940) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Stage Fright (1940) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Good Night Elmer (1940) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Bedtime for Sniffles (1940) - director (as Charles Jones)

- Elmer's Pet Rabbit (1940) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Sniffles Bells the Cat (1941) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Joe Glow, the Firefly (1941) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Toy Trouble (1941) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Porky's Ant (1941) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Porky's Prize Pony (1941) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Inki and the Lion (1941) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Snowtime for Comedy (1941) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Brave Little Bat (1941) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Porky's Midnight Matinee (1941) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Bird Came C.O.D. (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Who's Who in the Zoo (1942) - layout artist (uncredited)

- Porky's Cafe (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Conrad the Sailor (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Draft Horse (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Hold the Lion Please (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Squakin' Hawk (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Fox Pop (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Dover Boys at Pimento University or The Rivals of Roquefort Hall (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- My Favorite Duck (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Case of the Missing Hare (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- To Duck... or Not to Duck (1943) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Flop Goes the Weasel (1943) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Super-Rabbit (1942) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Unbearable Bear (1943) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Aristo-Cat (1943) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Wackiki Wabbit (1943) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Fin'n Catty (1943) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Inki and the Minah Bird (1943) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Tom Turk and Daffy (1944) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Bugs Bunny and the Three Bears (1944) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Weakly Reporter (1944) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Angel Puss (1944) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- From Hand to Mouse (1944) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Lost and Foundling (1944) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Odor-able Kitty (1945) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Trap Happy Porky (1945) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Hare Conditioned (1945) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Fresh Airedale (1945) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Hare Tonic (1945) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Quentin Quail (1946) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Hush My Mouse (1946) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Hair-Raising Hare (1946) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Eager Beaver (1946) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Fair and Worm-er (1946) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Roughly Squeaking (1946) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Scent-imental Over You (1947) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Inki at the Circus (1947) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- A Pest in the House (1947) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- House Hunting Mice (1947) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Little Orphan Airedale (1947) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- A Feather in His Hare (1948) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- What's Brewin', Bruin? (1948) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Rabbit Punch (1948) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Haredevil Hare (1948) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Rabbit Punch (1948) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- You Were Never Duckier (1948) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Daffy Dilly (1948) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- My Bunny Lies Over the Sea (1948) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Scaredy Cat (1948) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Mouse Wreckers (1948) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- So Much for So Little (1949) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Awful Orphan (1949) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Mississippi Hare (1949) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Long-Haired Hare (1949) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Often an Orphan (1949) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Fast and Furry-ous (1949) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Frigid Hare (1949) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- For Scent-imental Reasons (1949) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Bear Feat (1949) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Rabbit Hood (1949) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Homeless Hare (1950) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Scarlet Pumpernickel (1950) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Hypo-Chondri-Cat (1950) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- 8 Ball Bunny (1950) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Dog Gone South (1950) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Ducksters (1950) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Caveman Inki (1950) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Rabbit of Seville (1950) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Two's A Crowd (1950) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Bunny Hugged (1951) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Scent-imental Romeo (1951) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- A Hound for Trouble (1951) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Rabbit Fire (1951) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Chow Hound (1951) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Wearing of the Grin (1951) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Cheese Chasers (1951) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- A Bear for Punishment (1951) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Drip-Along Daffy (1951) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Feed the Kitty (1952) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Little Beau Pepé (1952) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Water, Water Every Hare (1952) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Beep, Beep (1952) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Hasty Hare (1952) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Going! Going! Gosh! (1952) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Mouse-Warming (1952) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Rabbit Seasoning (1952) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Terrier-Stricken (1952) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Don't Give Up the Sheep (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Forward March Hare (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Kiss Me Cat (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Duck Amuck (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Much Ado About Nutting (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Wild Over You (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Bully for Bugs (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Zipping Along (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Lumber Jack-Rabbit (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Duck! Rabbit, Duck! (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Punch Trunk (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- From A to Z-Z-Z-Z (1953) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Feline Frame-Up (1954) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- No Barking (1954) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- The Cats Bah (1954) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Claws for Alarm (1954) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Bewitched Bunny (1954) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Stop! Look! And Hasten! (1954) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- My Little Duckaroo (1954) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Sheep Ahoy (1954) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Baby Buggy Bunny (1954) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Beanstalk Bunny (1955) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Ready.. Set.. Zoom! (1955) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Past Perfumance (1955) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Rabbit Rampage (1955) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Double or Mutton (1955) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Jumpin' Jupiter (1955) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Knight-mare Hare (1955) - director

- Two Scent's Worth (1955) - director and writer (as Charles M. Jones)

- Guided Muscle (1955) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- One Froggy Evening (1955) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Bugs' Bonnets (1956) - director

- Broom-Stick Bunny (1956) - director

- Rocket Squad (1956) - director

- Heaven Scent (1956) - director and writer

- Gee Whiz-z-z-z-z-z-z (1956) - director (as Charles M. Jones)

- Barbary-Coast Bunny (1956) - director

- Rocket-bye Baby (1956) - director

- Deduce, You Say (1956) - director

- There They Go-Go-Go! (1956) - director

- To Hare Is Human (1956) - director

- Scrambled Aches (1957) - director

- Ali Baba Bunny (1957) - director

- Go Fly a Kit (1957) - director

- Boyhood Daze (1957) - director

- Steal Wool (1957) - director

- What's Opera, Doc? (1957) - director

- Ducking the Devil (1957) - director

- Zoom and Bored (1957) - director

- Touché and Go (1957) - director

- Robin Hood Daffy (1958) - director

- Hare-Way to the Stars (1958) - director

- Whoa, Be-Gone! (1958) - director

- To Itch His Own (1958) - director

- Hook, Line and Stinker (1958) - director

- Hip Hip-Hurry! (1958) - director

- Cat Feud (1958) - director

- Baton Bunny (1959) - director

- Hot-Rod and Reel! (1959) - director

- Wild About Hurry (1959) - director

- Fastest with the Mostest (1960) - director

- Who Scent You? (1960) - director

- Ready, Woolen and Able (1960) - director

- Hopalong Casualty (1960) - director and writer

- High Note (1960) - director

- Zip 'n Snort (1961) - director and writer

- The Mouse on 57th Street (1961) - director

- The Abominable Snow Rabbit (1961) - director

- Lickety-Splat (1961) - director and writer

- A Scent of the Matterhorn (1961) - director and writer (as M. Charl Jones)

- Compressed Hare (1961) - director

- Beep Prepared (1961) - director and writer

- Nelly's Folly (1961) - director and writer

- A Sheep in the Deep (1962) - director and writer

- Zoom at the Top (1962) - director and writer

- Louvre Come Back to Me! (1962) - director

- Martian Through Georgia (1962) - director and wrriter

- Now Hear This (1962) - director and writer

- I Was a Teenage Thumb (1963) - director and writer (as Chuck Jones Esq.)

- Woolen Under Where (1963) - writer

- Hare-Breadth Hurry (1963) - director

- Mad as a Mars Hare (1963) - director

- Transylvania 6-5000 (1963) - director

- To Beep or Not to Beep (1963) - director and writer

- Hare-Breadth Hurry (1963) - director

- War and Pieces (1964) - director

- Roadrunner a Go-Go (1965) - director (uncredited)

- Zip Zip Hooray (1965) - director (uncredited)

- Freeze Frame (1979) - director, producer and writer (uncredited)

- Portrait of the Artist as a Young Bunny (1980) - director, producer and writer

- Spaced Out Bunny (1980) - director, producer and writer

- Soup or Sonic (1980) - director, producer and writer

- Duck Dodgers and the Return of the 24½th Century (1980) - director, producer and writer

- Chariots of Fur (1994) - director, producer and writer

- Another Froggy Evening (1995) - producer

- Superior Duck (1996) - director, producer and writer

- Pullet Surprise (1997) - producer

- From Hare to Eternity (1997) - director and producer

- Father of the Bird (1997) - producer

- Daffy Duck for President (2004) - original story

- Private Snafu

- Coming!! Snafu (1943) - director

- Spies (1943) - director

- The Infantry Blues (1943) - director

- Private Snafu vs. Malaria Mike (1944) - director

- A Lecture on Camouflage (1944) - director

- Gas (1944) - director

- Outpost (1944) - director

- In the Aleutians – Isles of Enchantment (1945) - director

- It's Murder She Says (1945) - director

- No Buddy Atoll (1945) - director

- Going Home (unreleased) - director

- Secrets of the Caribbean (unreleased) - director

- So Much for So Little (1949) - director and writer (uncredited as writer)

- Orange Blossoms for Violet (1952) - writer

- A Hitch in Time (1955) - director and writer

- 90 Day Wondering (1956) - director and writer

- Drafty, Isn't It? (1957) - director and writer

- Adventures of the Road-Runner (1962) - director and writer

- Bugs Bunny and Daffy's Carnival of the Animals (1976) - director, producer and writer

- Bugs Bunny in King Arthur's Court (1978) - director, producer and writer

- The Bugs Bunny/Road-Runner Movie (1979) - director, producer and writer

- Bugs Bunny's Looney Christmas Tales (1979) - director and writer

- Bugs Bunny's Bustin' Out All Over (1980) - director and writer

- Daffy Duck's Thanks-for-Giving Special (1980) - director, producer and writer

Behind the scenes

- Joe Dante, who directed Looney Tunes: Back in Action, had a personal friendship with Chuck Jones, and had the latter make a cameo appearance in his 1984 film Gremlins. Jones would, in turn, create the title sequences for its 1990 sequel Gremlins 2: The New Batch.

Tributes

- In The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie, Bugs lists Jones as one of several "fathers" who contributed to his creation.

- In the 1984 film Gremlins, Jones appears as Mr. Jones, where he compliments a drawing of a vicious dragon that Billy drew, which the latter based it on bank mogul Ruby.

-

"You're doing fine."

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Chuck Jones". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ↑ Hugh Kenner; Chuck Jones (January 1, 1994). Chuck Jones: A Flurry of Drawings. University of California Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780520087972.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Martin, Hugo (February 23, 2002). "Chuck Jones, 89; Animation Pioneer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021.

- ↑ Jones, Chuck (1989). Chuck Amuck : The Life and Times of an Animated Cartoonist, New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux; ISBN 0-374-12348-9

- ↑ Jones, Chuck (1996). Chuck Reducks: Drawing from the Fun Side of Life. New York: Warner Books; ISBN 0-446-51893-X

- ↑ "Chuck Jones Interview – page 3 / 5 – Academy of Achievement". Archived from the original on July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Chuck Jones 1989 Interview | Animation Inspiration". YouTube.

- ↑ Jones, Chuck (1999). Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of an Animated Cartoonist. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-374-52620-7.

- ↑ Chuck Jones: Extremes and In-betweens – A Life in Animation (PBS 2000).

- ↑ Korkis, Jim (April 9, 2021). "Chuck Jones at Disney". Cartoon Research].

- ↑ Barrier, Michael (1999). Hollywood Cartoons. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 562–563; ISBN 0-19-516729-5

- ↑ Botwin, Michele (August 17, 2000). "Chuck Jones's Latest Creation Will Prowl the Web". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021.